Space? Property? Public? Private?

Editie: 23.3 - Verstedelijking

Published on: 10 juni 2016

Earth’s urban space is a cellular system that is also property, has fragmented into public and private, and becomes increasingly complex. Real estate, architecture and related disciplines have key roles in manipulating urban and urbanizing space.

|

Gordon Brown is Principal of Space Analytics in Wauconda (Chicago) and former Head of the Real Estate Group at TU/e. He has taught, written, consulted and done expert witness work for 30 years on problems concerning design and the built environment. As an expert witness, he has worked on multi-million dollar and leading cases in premises liability, architectural copyright, First Amendment public forum and problem property. He was Academic Fellow of the Urban Land Institute, professor of architecture at three major American universities, and the Aldar and academic dean at the Higher Colleges of Technology in the UAE. A Fellow of the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors, Dr. Brown has a BS from the University of Illinois, Urbana, an MBA from Penn’s Wharton School, MSc(Arch) from University College London and DTech from Ulster University. |

Real estate and architecture are divided by a common interest in space. The first space we gave conscious thought to was celestial and how we think about space on the earth’s surface may derive from our thinking about celestial space. Earth’s urban space is a cellular system that is also property, has fragmented into public and private, and becomes increasingly complex. Real estate, architecture and related disciplines have key roles in manipulating urban and urbanizing space.

0

Space

In Homeric Greece, Ouranos was space: the sky and the heavens. The earth, Gaia, was his consort. As reported in the Dictionary of the History of Ideas (Weiner 1973), Aristotle said space is inseparable from the matter contained in it. Soon after, Strato of Lampsacus said, “Some make space equal in extension to the cosmical body and declare it, though being void by its own nature, to be always filled with bodies and only theoretically to be considered as existing by itself.” This is absolute space. About the same time, Theophrastus said, “Perhaps space is not a reality by itself but is defined by position and order of the bodies according to their natures and faculties, as is the case with animals and plants and all non-homogeneous bodies … [that] have the nature of a structure.” This is relative space.

Physics, mathematics, psychology, computing, photography, geography, astronomy, economics, art, sociology, psychology, architecture, urbanism, real estate and others rely on their preferred concepts of space. Ways of thinking about space in architecture and real estate result in two different ways of representing space. Space in architecture is mostly geometric, three dimensional, relative and existential. Space in real estate is mostly geographic, two dimensional and absolute. As such, architectural and urban design is about the organization of relative space using visual and graphic representations, whereas real estate is about organization in absolute space using verbal and quantitative representations. The cellular character of public and private spatial configurations derives from relative space, space relative to our own being and interests.

0

Public and Private

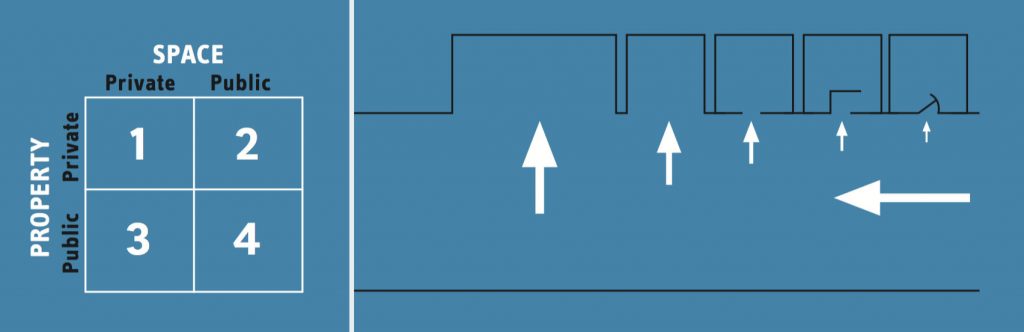

Private property can be a public space (like many shopping malls) and public property can be private space (like an office in a government building). Figure 1 left shows four combinations. Sometimes it’s difficult to distinguish private from public space. Geuss (2001) says civil inattention or disattendability determines what’s public. And Black’s Law Dictionary (1968) says about the same. (See figure 1 right)

“A public place is a place to which the general public has a right to resort; not necessarily a place devoted solely to the uses of the public, but a place …visited by many persons and usually accessible to the neighboring public. … Any place so situated that what passes there can be seen by any considerable number of persons, if they happen to look.”

|

| Figure 1: Left – Space/property combinations. Right – Five degrees of attendable space. |

0

How We Made Space and Property

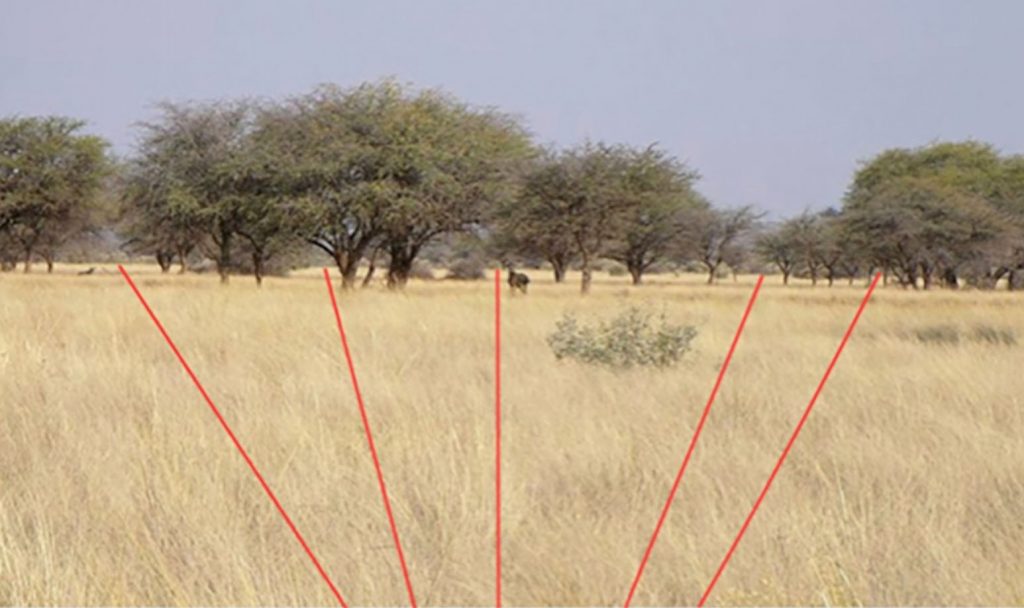

Most streets in permanent settlements worldwide from villages to major cities are arranged in a gridform pattern. Why? Pinker (1997) says we are adapted to two habitats. Our first choice, the East African savanna, is where most of our evolution occurred. The everyday spatial environment of developing humans over several million years was probably as transparent to them as water is to fish but we survived in savannas. Savannas, have features that are extremely appealing to humankind. Prospect-refuge theory (Appleton 1975) explains why.

“… at both human and sub-human level the ability to see and the ability to hide are both important in calculating a creature’s survival prospects . . . . Where he has an unimpeded opportunity to see we can call it a prospect. Where he has an opportunity to hide, a refuge. . . . To this . . . aesthetic hypothesis we can apply the name prospect- refuge theory.”

Prospect should be understood as something seen while moving ahead; refuge as a possible escape place along this route.

|

| Figure 2: Lines of prospect in a savanna. |

0

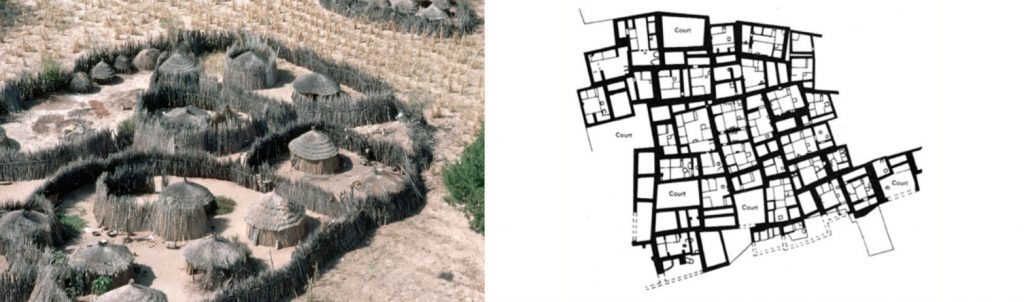

Developing humans were nomads for millions of years but we became fully human nomads at least 50,000 years ago. Nomadic people lived in temporary or conditional settlements. Settlement populations were usually less than 100 and would consist of bloodrelated families. Dwellings were typically round. Settlement borders/barriers were curvilinear. These pre-urban settlements provided refuge but not prospect. Refuge is within the walls but prospect is only outside the walls. There are no streets and real property – usually communally owned. See figure 3 left. It took at least 40,000 years before these fully human nomads would build permanent settlements.

|

| Figure 3: Left – Ovambo kraal in Namibia. Right – Çatal Huyuk, 6,000 BCE, > 5,000 people. |

0

Early permanent settlements were built in conjunction with early agriculture. Like temporary or conditional ones, early permanent settlements offered refuge but little prospect. See figure 3 right. Settlement populations over five millennia increased up to several thousand and most were related through clans. Dwellings and settlement borders were roughly rectilinear and refuge was inside dwellings and walls. But prospect was only outside the walls or atop taller buildings or those coincident with walls. There were a few courtyards but no streets; access to a dwelling was often through a roof hatch. Real property beyond the dwelling was communal.

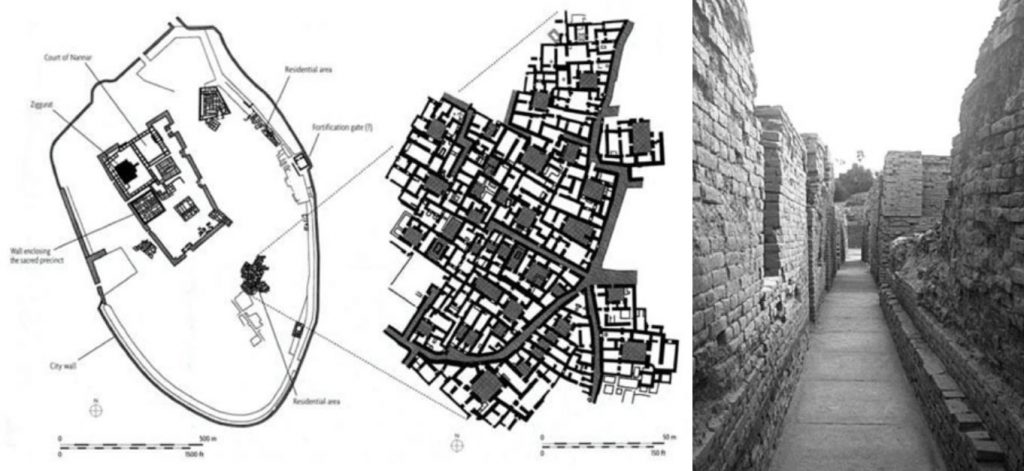

As trading increased after the agricultural revolution, permanent settlements could neither accommodate the increased movement nor enable monitoring of outsiders who came to buy and sell. Strangers were unrelated to anyone in the settlement and could be threats. Prospect was brought into the city in the form of streets. Figure 4. The first authentic cities were developed in Sumer about 3000 BCE. The city Ur had a population of thousands. Exterior barrier walls are rectilinear and curvilinear; dwellings are rectilinear and not part of barrier walls. Dwellings provide refuge and prospect is just outside dwellings along orthogonally arranged streets. The sacred district has rectilinear buildings and its barrier wall is rectilinear. Real property is no longer communal but owned by private entities (families) and the state.

|

| Figure 4: Left – A portion of Ur. Right – A street in excavated Ur. |

0

Pinker’s (1997) second choice for most of us is urban habitats. Why else would today’s massive urbanization and more people moving to cities happen? So how do prospect and refuge function in urban habitats?

The overwhelming majority of most permanent settlements worldwide, large and small, have buildings arranged orthogonally along grid-form streets. Streets, which became public or collective property, derive from prospect. Buildings, and the parcels they’re on, derive from refuge to become private property.

As we evolved, recognition of prospect and refuge became part of our neurological structure. Moser and other’s work (Solstad et al) shows head direction cells fire when certain land animals face in a certain direction, regardless of the animal’s position. A result is knowing prospect. Border cells fire when an animal is near its environment’s border, such as a wall or an edge. A result enables knowing refuge. Prospect and refuge arranged orthogonally into grid-form arrangements permit greater distribution of movement and inhibits paternalism and rent seeking in location selection. Grid-form street patterns are easy to scale thus enabling economies of scale. Movement in grid-form street systems has a natural logic with low cognitive load. Grid-form street systems, in contrast with curvilinear-dendritic systems developed after WWII, enable what Gigerenzer (2000) calls fast and frugal heuristics: “little trade-off between being fast and frugal and being accurate.” Grid-form arrangements require little reliance on geopositioning technologies. Because they are simple, enable density and route choice, and generate face-to-face potentials, grid-form street systems function as general purpose technologies (GPT) enabling economic growth.

|

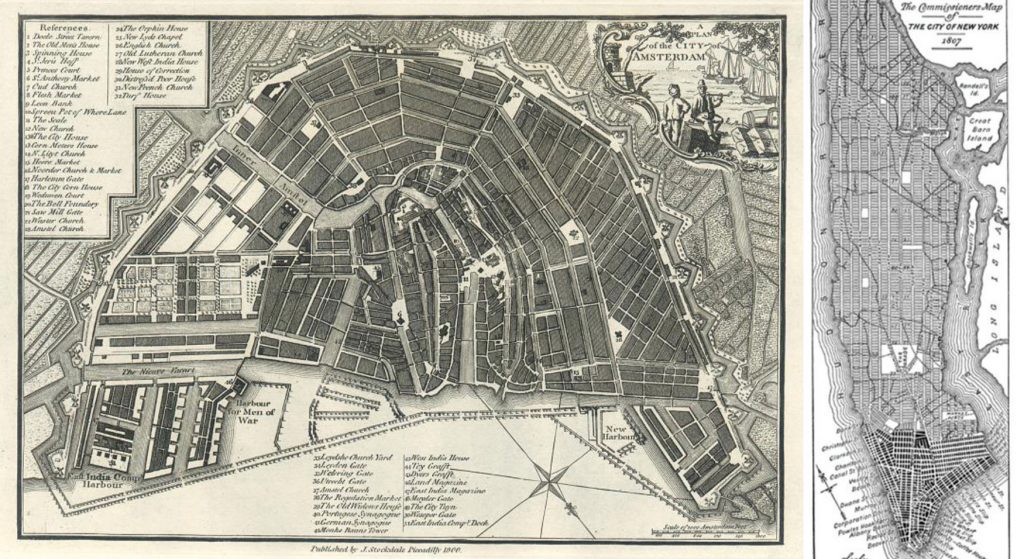

| Figure 5: Left – radial grid Amsterdam. Right – ultra grid Manhattan. |

0

Conclusion

A complex composition of public and private space and property, urban grid-form settlements evolved through a slow, trial and error and anonymous design process taking over ten millennia. We take them for granted. A grid-form street system is not a tessellation; it can be bent, overlaid with radial streets, and threaded by curving grand boulevards. Urban development over the past five to ten decades has been either uncontrolled in many nations or consciously designed which, through a combination of moral design and industrialized finance, has eroded efficacies of urban form that have developed over millennia. Current efforts to create smart cities are not without merit, but smart cities need smart urban form.

0

References

Appleton, J. 1975. The Experience of Landscape. London: John Wiley.

Arnheim, Rudolph. 1976. The Dynamics of Architectural Form. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Black, H. C. 1968. Black’s Law Dictionary (Revised 4th edition). St. Paul, MN: West Publishing.

Brown, M. Gordon. 2016. Access, Property and American Urban Space. New York and London: Routledge/Taylor & Francis.

Geuss, R. 2001. Public Goods, Private Goods. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Gigerenzer, Gerd. 2000. Adaptive Thinking: Rationality in the Real World. New York: Oxford University Press.

Piaget, J., and B. Inhelder. 1972. “The Child’s Conception of Space.” In The Essential Piaget. Edited by H. Gruber and J. Voneche. New York: Basic Books, pp. 576–642.

Pinker. S. 1997. How the Mind Works. Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin.

Solstad T, C. N. Boccara, E. Kropff, M-B. Moser and E. Moser. 2008. “Representation of Geometric Borders in the Entorhinal Cortex.” Science 322: 1865–1868.

Van de Ven, C. 1987. Space in Architecture: The Evolution of a New Idea in the Theory and History of the Modern Movements (3rd revised edition). Assen/ Maastricht, Netherlands and Wolfeboro, NH: Van Gorcum.

Weiner, P. P. 1973. Dictionary of the History of Ideas. Vol. 4. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

[1] This story was first presented at TU/e during Dutch Design Week, October 2015. Much of this text derives from Mr. Brown’s book, Access. Property and American Urban Space, published March 2016 by Routledge/Taylor & Francis.